My Identity Struggle Became My Freedom

Name: Lisa Atia

Title: Growth strategist

Purpose of work: Building communities of people-of-color-led companies and founders

My whole life, I’ve had mixed feelings about being mixed race. Not because I was embarrassed to be either race — there were just so many seemingly contradicting layers to my existence. Growing up in L.A. in the ‘80s, there were very few, if any, biracial kids where I lived. On top of that, I only knew my Egyptian side (my mother being Eastern European). I never knew what to fill out on my test scantrons in school, always having to mark the “Other” box (and sometimes that wasn’t even an option). That was the start of seeing myself as just that — “Other.”

The strange thing though, I almost always identified with only one-half: the Egyptian half. This was the half after which the curve of my hips and the darkness of my features resembles; the half of me that was raised in a strict old-school Coptic, Egyptian household in which we were taught about our people and our culture at every meal. My mother’s family was never as close and we never got to know them. My mother became baptized Coptic Orthodox before marrying my father, so that further rooted her identity into my father’s very large family — and therefore, further away from hers.

All of our parents make choices as adults, and those choices ripple onto their children’s lives, the significance of some taking time to fully recognize.

GROWING UP DIVIDED

I remember growing up in two very distinct neighborhoods. The first, where I spent most of my waking hours in childhood and early adulthood, was in a predominantly Black neighborhood. All the grandparents — as well as most of my immediate aunts, uncles and cousins — all lived within a few miles of each other, which, if you know anything about Egyptian culture, means you can pop up at anybody’s house at any time. Meaning, we were always together. This is where we spent weekends, weeknights, summers. It was the kind of neighborhood where we all played outside and the adults up and down the block would look out for one another’s kids (and call my grandma on me if I did something wrong). A village it was. It was here our neighbors celebrated our culture — they loved learning about Egyptian culture, always curious about our traditions. The neighborhood felt like an extension of my family.

Then there was the neighborhood in which we lived. The neighborhood in which my parents paid 16% interest on a house just to get us into the “best” school district. We were the only mixed family, much less people of color, in the area. Everyone else was White. We were looked at differently and taunted in school. My parents were met with hate and discrimination — notes on their cars along with zucchini and salt, because those ate away at the paint. All in an area 15 minutes away from my true home.

It was in that city that I learned I was hated because of where I came from. It was there I learned that being different was now somehow a disadvantage. It was there that confusion around my identity started to take root, and I didn’t even know it yet.

STRICT AS AN UNDERSTATEMENT

Like many immigrant parents, my sisters and I grew up incredibly sheltered and fiercely protected by our parents, making sure we were in no way influenced by American culture. (This in of itself was always fascinating to me given that my father immigrated here at 19 to give himself and his family a better life, all the while finding a myriad of things to despise.) If we claimed an identity other than Egyptian, we were lectured for hours (by both parents) about what it took for our family to get here, how we will always be “different” than everyone else, to be proud. As a teenager, these differences stifled my sense of belonging because it meant no school dances, no wearing tank tops in summer, no dating, and definitely no dating outside of our race and ethnicity.

“Hey Dad, but we’re half-white and half-Egyptian; are you saying we need to marry someone who is half and half like us?”

“Don’t act silly, Lisa.”

Care to elaborate, pops? Nope, I got nothing. It only made my father angrier when I asked questions. Even my mother had no idea what to say to me, which I later came to find out was because she didn’t even know what my father meant either. We had to take what he said at face value. To make things more complicated, we were the only biracial family in our entire extended family, so it’s not like we had anyone to compare our experience to or from whom we could have some semblance of empathy or understanding. No wonder I wasn’t comfortable in my skin. I didn’t know who I was allowed to be.

It was in that city that was supposed to be “better” where I learned to be ashamed of some part of myself. It showed up in what I allowed in relationships, in how I saw myself, and in my perception of self-worth and outward success. The controller in me wanted to shape my life exactly as I wanted it out of selfishness. I was in a constant state of pushing, striving, and I felt as fake as I’ve ever felt. I worked against myself for years and got nowhere.

NOT DARK ENOUGH, NOT LIGHT ENOUGH

As I grew up, the confusion continued for obvious and not-so-obvious reasons, one of them being I never really “belonged” in any group (I’m sure the story is familiar to many — I was too “White” for the Egyptians and I was too Egyptian for White people).

As the oldest of three daughters, I felt immense pressure. On top of familial pressure to be the perfect, pious daughter, I also had to figure out how to fit into and thrive in this American culture in which I wasn’t allowed to partake. All the while having to navigate puberty; crushes with non-half-Egyptian, half-white boys; saying no to all the cool parties; conscious of what my choices meant within and outside of my family. So, like many children of immigrants, I led a secret life. I snuck out, had sex and dated boys outside of my race, everything that if my parents found out about, would surely send me back to the motherland.

Growing up in a strict household created a sense of resentment, resentment that led to this deep internal struggle not only with how much of myself to put out there, but with how much I wanted to identify with a culture that told girls they were born to get married, breed, and spend all day cooking for your husband. As I’ve thought about this over the years, I recognized a fascinating dichotomy: as much as my parents were traditionalists, there were fiercely adamant about pushing education and independence on me and my sisters — as long as it didn’t come up against their ideals and didn’t shatter their belief system.

Identity became more complicated as I grew up and grappled with becoming a woman. There were many things that I loved about being Egyptian but that I also hated about being mixed race. I wanted to be an independent strong woman, but I also wanted to be loved and to have relationships that mirrored those family communities I admired so much. I always felt at odds with myself. I spent most of my 20s figuring out how much of myself I could truly embrace publicly — especially after 9/11. As you probably know, everything changed here for people who look anything like me. That is a pain and a story for another time.

FINDING MY IDENTITY

I decided to visit Egypt as an adult.

I showed up expecting society to be as strict as my father’s standards. However, I quickly came to see — with their tank-top-in-summer-wearing-girls — that even Egypt had progressed with the times, but my father’s idealized version of where he grew up did not.

That revelation changed me. I realized I had the right to be whomever I wanted to be and not in secret either. It made me bold. I gave myself the permission to finally be me. If these girls who grew up in this ultra-strict, religious society could make up their own minds about how they wanted to live life, then dammit, so could I, and I was going to go balls to the wall.

Now, my once “Otherness” defines me. My Egyptian-ness defines me. My Egyptian family and upbringing defines me — my loud, intrusive, loving, very large Egyptian family. That first neighborhood, my true hometown, defines me. I can finally say I’m thankful for all the experiences I had growing up — each one gave me a perspective so varied from the norm that it has allowed me to realize the struggle that runs through all our veins, behind every closed door, in every family.

There is a part of me that still feels guilty about not really knowing or understanding one half of myself. Even as a teenager, I didn’t understand why my mother left behind her family to become “Egyptian.” But I get it now. Her family was never really a family, not in the sense of what we were lucky enough to be. That extended family? My family is a tribe for real. We do everything together. It’s annoying and yet incredibly humbling to know that you will always have a group of people that love you, support you and will be there to do that high-pitched tongue trill thing at every celebration (which is both embarrassing and inspiring).

These days, I look forward to the family dinners and the big gathering at Thanksgiving. I anticipate my grandmother’s grapeleaves, the cousins getting together for a drunk game of Taboo, the men sitting outside smoking hookah while the women sitting in the living room drinking tea, gossiping and watching the latest Arabic soap opera. It’s taken time and some deep soul-searching to come to terms with my identity. But now? I am a proud Egyptian American woman.

AND THEN, PURPOSE.

And for the first time in my life, I had faith in what I was called to do because I was no longer in turmoil about who I was. And as my confirmation, my purpose revealed itself in the work I attracted. Equity. Justice. Fighting for others to receive the opportunity to have that same revelation about themselves, about their communities.

Now I can see every experience molded me into this person who uses the lessons learned to drive toward building up communities, building up leaders, all of who look like me. We all may not have gone through the same experiences but we’ve each lived a familiar pain. Each of us has a different walk. Mine isn’t going to look the same as yours. But we experience the same feelings of loss, hardship, joy, excitement — and depending on which you use for your motivation, depending on what you really believe in, it can either get you out of bed in the morning or keep your talents hidden from the world.

No longer do I view my upbringing as something to be ashamed of, but instead, my perspective has shifted into one of gratitude. My challenges, every one of them taught me a valuable lesson. I now have a fight in me that isn’t just for myself, but for others who can’t yet hold themselves up, even for themselves. But they will and when they do, they’ll do it for the next human being who yet can’t. That’s how we build community, by building up one person at a time.

A POEM

BY LISA ATIA

“Roots Run Deep”

It’s in the curve of my lips

And in the width of my hips.

It’s in the almond shape of my eyes

And in the thickness of my caramel-colored thighs.

You’ll hear it in the depths of my voice

As I hum the tune of my ancestors roars,

Kings and Queens, jewels on their necks, heads and wrists adorned.

You’ll find hints of it in the spices I use to make your tea

Warming you from a place where the deserts storm.

It connects us as we long for something we can both feel

A deep belonging, a need to be heard, seen, known - real.

A truth that’s beyond videos, pictures, the things we use as invisible shields.

We use a shield to mask hurt that is pushing up just beyond the surface of our skin.

A hurt that could take us into a depth beyond the judgment of our shared sin.

You’ll find it in the hours spent preparing a meal in which we share together

As we laugh, talk shit, and talk real.

It’s in the blood that runs through our veins

thousands of years’ worth of stories of trials and tribulations

A history, stained.

It is the triumph that can only come from deep roots.

No judgment of skin tone, to divide and separate

It remains in the strands of our shared DNA.

It is our royalty, our inheritance,

To build from a foundation of truth, from a place of abundance, of gain.

On that we stand, to build for tomorrow,

Starting with the work of our hands today.

Lisa Atia is a 2018 Startup Coach for the Camelback Fellowship. She will be the MC for our 2018 Showcase.

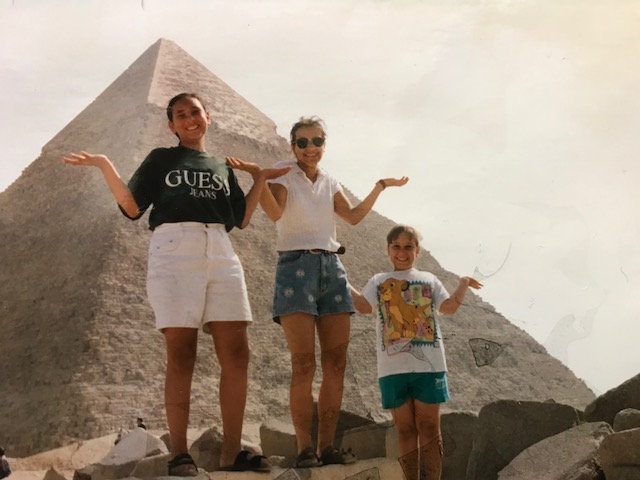

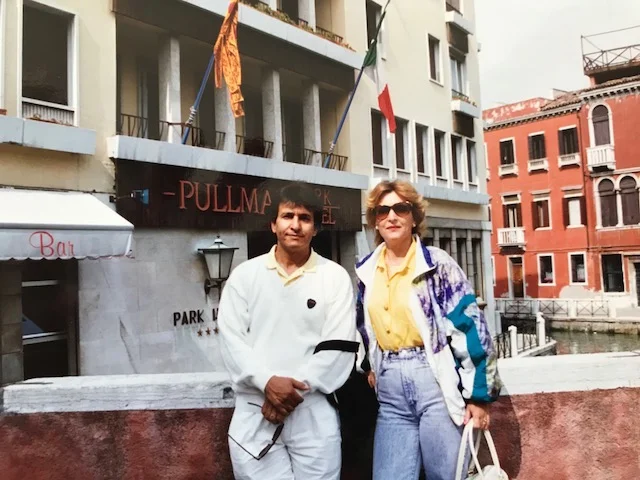

All family photos are courtesy of the writer.

![Lisa at New Orleans Entrepreneur Week in 2017 presenting on a keynote on communications and brand strategy. [The Distillery.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57e2d6ab440243c69eb9cb95/1537829562175-724KAJ1HLNV1LNKJX6A6/Lisa-Atia1-800x600_noew.jpg)